Will this year "leap" India into the superpower league? (A Leap Year Post)

India has it’s odds stacked in it’s favor. But is India making use of it?

By Sneha Susan Jacob

Background: With the supply slowdown that happened in the early 2020s, Supply Chain strategists are trying their best to create resilient supply chains. Talks about offshoring, reshoring, nearshoring and friendshoring have started cropping up in every conversation, off late. These words came around as a solution to the supply chain disruptions that we have faced over the past decade. However, the question remains if these loosely thrown around words carry any value?

Trade, if voluntary is a positive sum game and would lead to a prosperous society. At the recent TradeTech forum hosted by the WEF and the UAE government, statistics shared, proved the above statement, “In 1990, almost 40% of the global population lived in poverty. With trade, this number changed to less than 10% even with a massive spike in population over the same period (5 Billion People —> 7 Billion People).”

In addition, everyone should be playing to their comparative advantage. If we aren’t, we would be looking at price hikes across the value chain. As a Supply Chain professional, my role is to make the value chain efficient and effective and my go-to strategy would be to employ Friendshoring with a bit more backing to that term than just the fact that the country is an ally. Which technically also means that India won’t be my immediate choice yet.

History:

GDP per Capita: There were countries which were on par with us - China, Japan and Korea at some point of time (The Wire shares a good representation of this). China and India had common starting points, however the paths taken map the major areas of differences (Primary and Secondary axis on the chart below).

The Rural Divide: As much as the there were a lot of post-1978 reforms which worked in China’s favor - one key economic reform was seen in the rural sector. Reforms expanded property rights in the countryside and ignited a race to form small nonagricultural businesses in rural areas. Decollectivization and higher prices for agricultural products led to more productive (family) farms and more efficient use of labor. These forces also, induced many workers to move out of agriculture. The resulting growth of village enterprises drew tens of millions of people from traditional agriculture into higher-value-added manufacturing.

With greater autonomy granted to enterprise managers, the welcoming of foreign investments (<1% of total investment in 1979 —> 18% in 1994), economic liberalization and strong export growth during the same period, led to the economic transformation in China.On the other hand, economic liberalization in India transformed the life of the urban Indian but left the rural Indian behind. India’s GDP increased at 7-9% starting in the mid-1990s, but agricultural growth averaged only 2.5-3.5%. The sector’s contribution to GDP declined from 23% in 2003-04 to about 14.6% in 2018, without a corresponding reduction in the population dependent on farming and related activities. The ratio of farm to non-farm incomes has worsened from 1:3 to 1:5, resulting in increasing rural indebtedness and marginalisation.

The Rural Divide further played into impacting a couple of other factors:

A Healthy Population: China was primarily an agricultural economy. Decollectivization happened due to the increase in R&D investments that had farmers producing more from plots averaging 0.6 ha in the 1990s, compared to 1.4 ha in India. This in turn increased the per capita food supply by almost 1,700 kilocalories per day between 1961 and 2013, compared to about 440 kilocalories in India. Daily per capita protein supply in India over the past half century increased by only about 8 gm compared to nearly 60 gm in China. A healthy economy was the reason behind China’s sucess whereas India suffered with almost 200 million undernourished in the rural areas, thus impacting GDP.

An Educated Population: As much as India’s manufacturing sector isn’t as high as it’s current counterparts (Image 1), we do have a fair services sector. As against the manufacturing sector, the services sector is education intensive. With the education levels in South Asia, India can’t absorb the workers from the rural areas into it’s services sector just yet (Image 2). As much as there is a debate on whether the focus should shift to the services sector against manufacturing - primarily, due to the change of scope of services from “flipping hamburgers, now we have to think of services as rocket science” - economic growth for India would always stem around manufacturing due to the fact that the existence of services is largely dependent on a strong educated population. And all of this wouldn’t be possible without a healthy population.

Present: With the above data, it is clear that manufacturing would definitely boost a section of our society out of poverty and India has had a couple of initiatives mapped to making India a manufacturing hub.

Make In India Campaign: The “Make In India” program was a program launched by the Indian government with the aim of boosting manufacturing and increasing FDI. It had a goal of raising the manufacturing share of GDP to 25% by 2022, which was later revised to 2025. By 2022, India reached 13%, a decrease from the years before that. The S&P Global Market Intelligence mentions that there was a spike in the next financial year to 17% and the Hindu mentions a 16% (data inaccuracies).

FDI Mapping: The below graph shows the inflow of FDI across several years and the greatest sectors impacted by the FDI are the services and the software and hardware sectors. This reflects a certain trust on the Indian economy and it’s ecosystem.

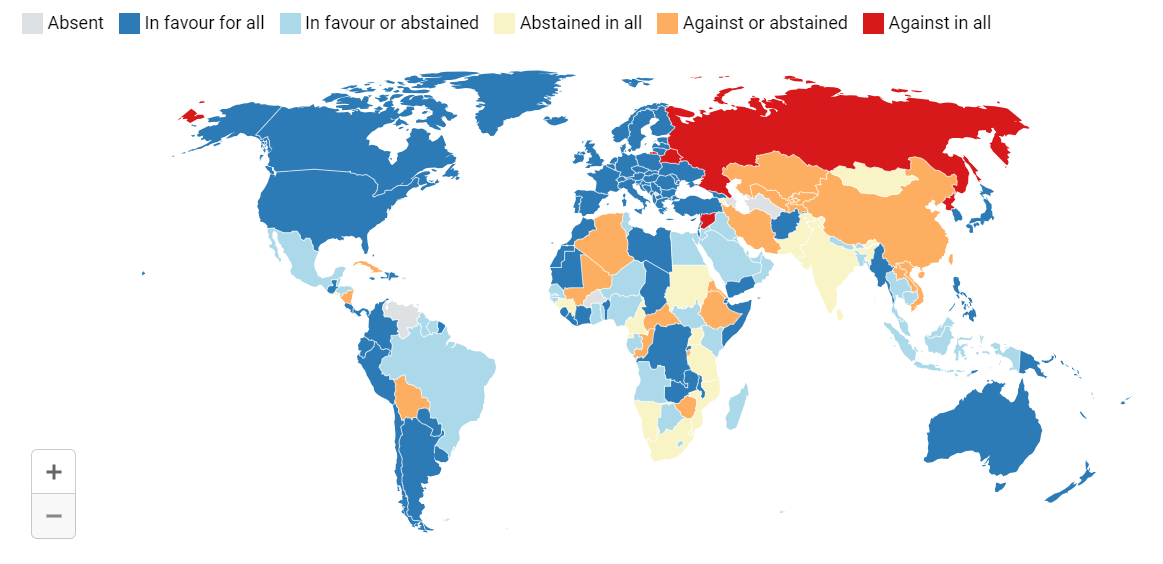

Being an Ally: As much as the FDI inflow hit a peak in FY22, there was a dip in FY23 and this moves along the lines of being an ally. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the world split itself into different categories - with Ukraine, with Russia and impartial. The for and against are not just slated as a vote at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) but also by providing military assistance or even imposing sanctions. I mean, if you’re my friend - you’re either with me or not.

The Triple E: Not a lot of data was openly available to assess the initiatives from a perspective of efficiency, effectiveness and equity. With manufacturing in industries like telecom, moving from net deficit to net surplus in a decade and the reflection on the same in the electronics sector, India has proved itself from a manufacturing capabilities standpoint. However, the question remains - does this impact the small and medium enterprises, would it cause the growth spurt required and would this generate jobs in states which require it.

Future: The decades of growth that China has grown on, can’t be replicated overnight in any region. The FDI inflows reflects the trust in India and it’s capabilities. Different policies like the PM GatiShakti, PLI Scheme, Export promotions and the liberal FDI norms show that India is opening it’s doors to the world. Though for us to get to a position to become a connector economy, we have a long way to go to fill in the gaps lost in the past decade and to find our footing in terms of what we believe and I do believe this decade would be one that could help change that for India.

Sneha Susan Jacob is currently a student of the GCPP (Defence and Foreign Affairs) Programme and she writes a newsletter called That Purrfect Life. Read the original piece here.